Rethinking U.S. health spending

Rethinking U.S. health spending

July 25, 2023 | By Dean Sevin Yeltekin

In this Q&A, Senior Lecturer Sam Ogie examines the key drivers of U.S. health spending and makes the case for equipping health professionals with the management skills they need to shape the future of their industry.

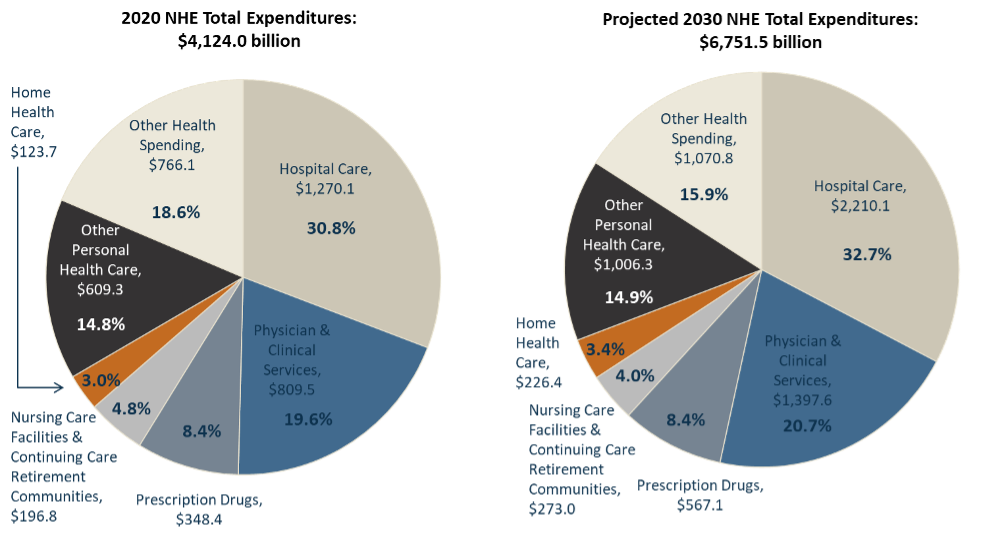

The COVID-19 pandemic was an earthquake that rapidly reshaped the U.S. healthcare landscape, and we are still experiencing the aftershocks. Health spending in the U.S. reached $4.3 trillion, or $12,914 per capita in 2021—lower than a historic high in 2020 but still above pre-pandemic levels.

U.S. Health Spending: 2020–2030

Sam Ogie, a Senior Lecturer, and the Faculty Director of the Medical Management Program at Simon Business School, joined our faculty in 2007. Having worked previously in the healthcare consulting arena, he offers a rich perspective on the business challenges that confront today’s healthcare providers.

In Part 1 of this Q&A, I asked Sam to tackle the complex topic of U.S. health spending. Below, he unpacks the lead drivers of spending and explains how Simon is preparing healthcare professionals to deliver sustainable, high-quality care in a changing environment.

What are some of the key business issues confronting healthcare providers in 2023?

Hospital CEOs consistently point to workforce challenges as their top concern. They are facing mounting financial challenges as they must increase wages to fill the gaps left by pandemic burnout, vaccine mandates, and shutdowns. With the rise of travel nursing, the nursing sector has been hit particularly hard. When travel nurses are paid twice as much as staff nurses, that is a strong incentive for staff nurses to quit and very little incentive for nursing school graduates to replace them. The healthcare system is still reeling from the pandemic, and nowhere is this more evident than in the workforce. It will take some time for things to settle down.

A second major challenge is navigating the industry-wide shift from a fee-for-service model of care, which reimburses healthcare providers based on the volume of services provided, to a value-based model of care, which links reimbursement to quality of care provided. This shift is happening more slowly than anticipated for a few reasons. First, it is exceedingly difficult to measure value. Two patients receiving an identical treatment can have two different outcomes for unknown reasons. Second, it’s not clear that pivoting to value-based care will actually lead to cost savings for providers. Providers are still preparing to make the shift—they have no other choice when Medicare, their largest payer, is pushing it—but fee-for-service still constitutes the majority of payments today. Providers’ financial and operational success hinges on their ability to manage risk in this transition.

What is the primary driver of increased healthcare spending in the U.S.?

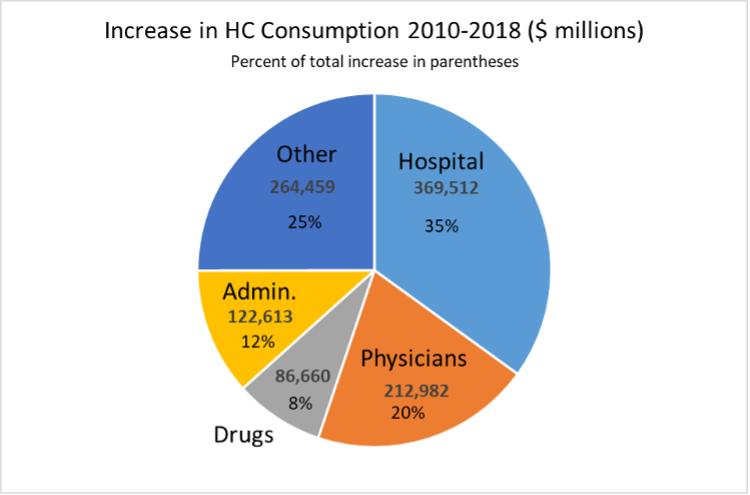

A 2021 analysis by the American Hospital Association found that increasing use and intensity accounted for the majority of the increase in spending. In other words, Americans are consuming more of the same services and more costly, intensive services. This matches a meta-analysis published by the Congressional Budget Office that found that increasing utilization and higher technology accounted for between 40-65% of the increase in per capita healthcare spending growth from 1940-1990.

If you asked the average American about the primary drivers of healthcare spending, they would likely point to the cost of drugs. Despite what headlines would lead us to believe, drug spending is actually a small, stable percentage of spending. According to the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), drugs only accounted for 8% of the growth in spending on health care consumption from 2010-2018. Spending on hospitals accounted for 35% and physicians 20% of growth. NCHS is projecting that drugs will remain about the same share of national health expenditures through 2030.

Overall healthcare spending is on a sustainable trajectory. Medicare, unfortunately, is a different story. Any money left over after paying for the healthcare of existing beneficiaries is spent elsewhere and the government gives Medicare an IOU. As the number of Medicare enrollees climbs, so does the pile of IOUs that there are no funds to cover.

In your view, is U.S. health spending too high?

I disagree with the sentiment that the U.S. spends too much on healthcare. I frequently remind my students that even after accounting for health spending, Americans have more per capita wealth than Canada, the UK, and other OECD countries. One of the reasons health spending is higher in the U.S. is that our physicians and nurses earn far more than their counterparts in other countries. For example, according to the U.K. NHS, the salary range for GPs is L65 – L98 or $83-125K. The average pay for a nurse in NY state is $93k and $124k in CA. These higher salaries reflect the fact that American professionals across the board out-earn their counterparts in other countries. If we attempt to push down these wages in a bid to cut health costs, we will have a harder time convincing talented, hardworking young people to invest their time and money into pursuing a career in healthcare. Higher wages translate into higher healthcare costs, but that is the price of delivering excellent care.

Do U.S. health outcomes justify higher levels of spending compared to other wealthy countries?

There is a public perception that the U.S. spends much more than other OECD countries yet still achieves inferior outcomes in terms of life expectancy and other metrics of health. When we dig a little deeper, we quickly uncover obvious reasons that the U.S. is an outlier.

First, on the outcomes side, the United States has much higher rates of violent death than most of the OECD countries. While homicides, suicides, and motor vehicle accidents are tragic and deserve careful scrutiny, it would be unfair to link all these things to health spending rates. If we adjust for these factors (i.e., standardize the rate of violent death), U.S. life expectancy is the highest in the OECD. Second, the U.S. healthcare system delivers excellent outcomes for patients once they are diagnosed. For example, the U.S. ranks at or near the top in five-year survival rate for the most common types of cancer. Third, a good share of U.S. healthcare spending goes toward care that does little or nothing to increase life expectancy but still offers significant value to patients. Relatively quick access to a knee replacement is unlikely to increase an individual’s life expectancy, but it certainly does reduce their pain and improve their mobility. Life expectancy, then, is a useful but limited metric to examine the value of a healthcare system.

You serve as faculty director of Simon’s Medical Management Program. What market need does this program fill?

It is far easier to take someone with clinical knowledge and teach them to be a good manager than the other way around. The Medical Management Program was launched 20 years ago to ensure that physicians, nurses, pharmacists, hospital administrators, researchers, and other industry professionals approach patient care with solid management skills and a nuanced understanding of the business side of healthcare.

Since the creation of the program, the demand for flexible, digestible educational content has only increased. We are currently developing stackable certificates in finance, marketing and strategy, operations and analytics, and leadership to give students more options that fit their schedule and offer usable insights in a condensed period of time.

How can Simon continue to improve upon its efforts to shape a new generation of healthcare leaders?

There will never be a shortage of healthcare professionals who can benefit from learning management skills, but accommodating their need for flexibility presents unique challenges. The world is rapidly shifting to online, asynchronous education. Down the road, we aim to develop more online offerings to expand our reach without compromising educational quality. We will continue to partner with the University of Rochester Medical Center (URMC), working in tandem to develop curriculums that prepare healthcare professionals to confront the most seemingly intractable challenges of our time.

Samuel Ogie is a Senior Lecturer and the Faculty Director of Simon's Medical Management Program.

Follow the Dean’s Corner blog for more expert commentary on timely topics in business, economics, policy, and management education. To view other blogs in this series, visit the Dean's Corner Main Page.