Whatever it Takes

Whatever It Takes

September 25 | By Professor Professor Alan Moreira

In this blog, Professor Alan Moreira unpacks the effects of policy promises on financial markets.

In 2012, Mario Draghi, then president of the European Central Bank, mentioned in a speech to a group of hedge fund managers that he would do whatever it took to save the euro. That remark alone dropped bond yields across Europe. In March 2020, the Federal Reserve announced purchases of corporate bonds but ultimately purchased only $15 billion worth. It didn’t matter—the market responded by increasing valuations to the tune of $1 trillion.

The central issue for policymakers is whether it was the $15 billion dollar intervention that created the massive $1 trillion dollar wealth creation, perhaps because markets were extremely illiquid, or if the market was responding to expectations of much larger interventions in the future. Understanding how the policy announcement worked is essential to perform a proper cost-benefit analysis of these policies.

In “Whatever It Takes? The Impact of Conditional Policy Promises,” my co-authors and I present a framework to measure how exactly these announcements impact financial markets.

Measuring Promises

The framework we created establishes how to use option prices to learn how the market thinks about a particular announcements. Options, because they pay in some scenarios but not others, give us a snapshot of expectations—i.e., what the expectation is that the price is going to be at a certain level in one month, three months, six months, etc. By looking at the price of these options, we can measure what the market thinks the distribution of this price will be over a certain length of time, just not at one point in time.

Our paper demonstrates how to use this classic insight in finance theory and apply it to policy announcements. The key idea is that option prices allow us to measure the price distribution before and after the announcement, which gives us a model-free way of measuring in which scenarios the policy change prices and by how much.

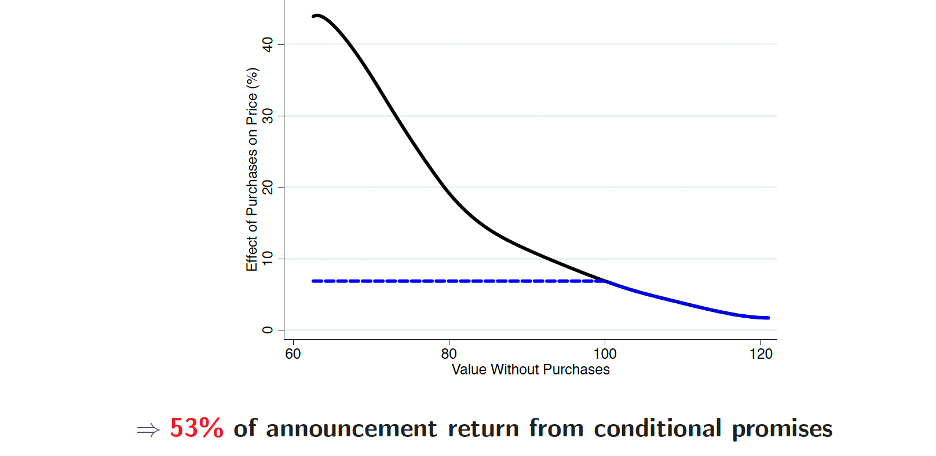

In Figure 1 (below), the black line represents the effect that a policy has on price in different states of the world, measured here in terms of the price of the underlying asset in some near future. A value of 60 means the asset would have lost 40% of its value absent the intervention. The black line shows the effect of the announcement for each of these realized price states. We see clearly that the policy worked by providing much more price support in very bad scenarios—scenarios where prices would have dropped by as much as 40%. This shows that the policy works very asymmetrically and cuts against the view that it was the $15 billion dollars by itself that did the trick. Rather, it suggests it was expectations of much larger interventions in these terrible scenarios that explain the dramatic price response to the announcement. The data tell us that the market sees the announcement as the Fed giving it a put option.

Promises Matter

To get a sense of how important this “Fed Put” is for asset prices, we look at the following counterfactual exercise. The blue represents a different policy that offers the same support for all prices below the current price, i.e. it does not have this “Put” component. The black line signifies downside support, like when the Fed intervenes to buy corporate bonds in a downturn.

For the unprecedented corporate bond interventions in 2020, this “Put” component explains more than 50% of the price response, i.e. if market thought the Fed would intervene at the level of the blue line instead of the black, returns would be 50% lower than what we saw.

We also look at a broad cross-sectional of interventions, extending our analysis beyond the Fed to other policy announcements in the UK, Euro area, and Japan and found that the effect on the market would be 20% smaller if people didn’t expect government intervention in a worse state of the world.

In other words, the expectation of future intervention is essential to understand why these announcements can have such powerful effects in financial markets.

Communication Matters

The Fed framed its policy as aimed at fixing “dysfunctionality” in financial markets. Consistent with this view, at the onset of the intervention corporate bond prices completely disconnected from traditional measures of fundamentals as implied by interest rates and bankruptcy risk, which can be measured in real time using bond prices and prices on credit default swaps. We can apply our methodology to figure out if the intervention acted in states where bond prices were low due to interest rate risk, bankruptcy risk, or due to a disconnect between bond prices and fundamentals. We find that the market response was entirely consistent with the Fed view: Option prices show that the Fed was expected to intervene almost exclusively in states where prices were low because markets were dysfunctional.

The Long Ripples of Intervention

Consistent with these announcements shaping investors’ expectations of future interventions, we see traces of announcements in asset markets long after they are made.

For example, after the Fed announced that it would buy corporate bonds, but long after the policy official ceased, we can measure a dramatic change in relationship between corporate bond markets and equity markets. Prior to intervention, these markets tended to move in the same direction. After intervention, this link was broken because the central bank rescued corporate bond markets and but not equity markets. This suggests that expectations of intervention makes measures of corporate bond risk less reliable than before.

In the context of Quantitative Easing policies that many central banks pursued, we see a related phenomenon: The response to the first announcements were sizable. But then, as time went by, the effects of policy interventions on the market became smaller and smaller until they became negligible. Some analysts took this to mean that the right way to measure the impact of a policy promise is just to measure the impact of an initial announcement. What they miss is that the first announcement encodes all the future ones. In other words, the market effect of the first announcement factors in the effects of all expected future interventions. Thus, costs of these future announcements have to be included in the cost-benefit calculation as well.

Alan Moreira is an associate professor of finance at the Simon School of Business.

Follow the Dean’s Corner blog for more expert commentary on timely topics in business, economics, policy, and management education. To view other blogs in this series, visit the Dean's Corner Main Page.