Why Americans are so unhappy with the economy

Why Americans are so unhappy with the economy

September 11 | By Professor Narayana Kocherlakota

Professor Narayana Kocherlakota points to real wage decline to explain widespread voter pessimism about the U.S. economy.

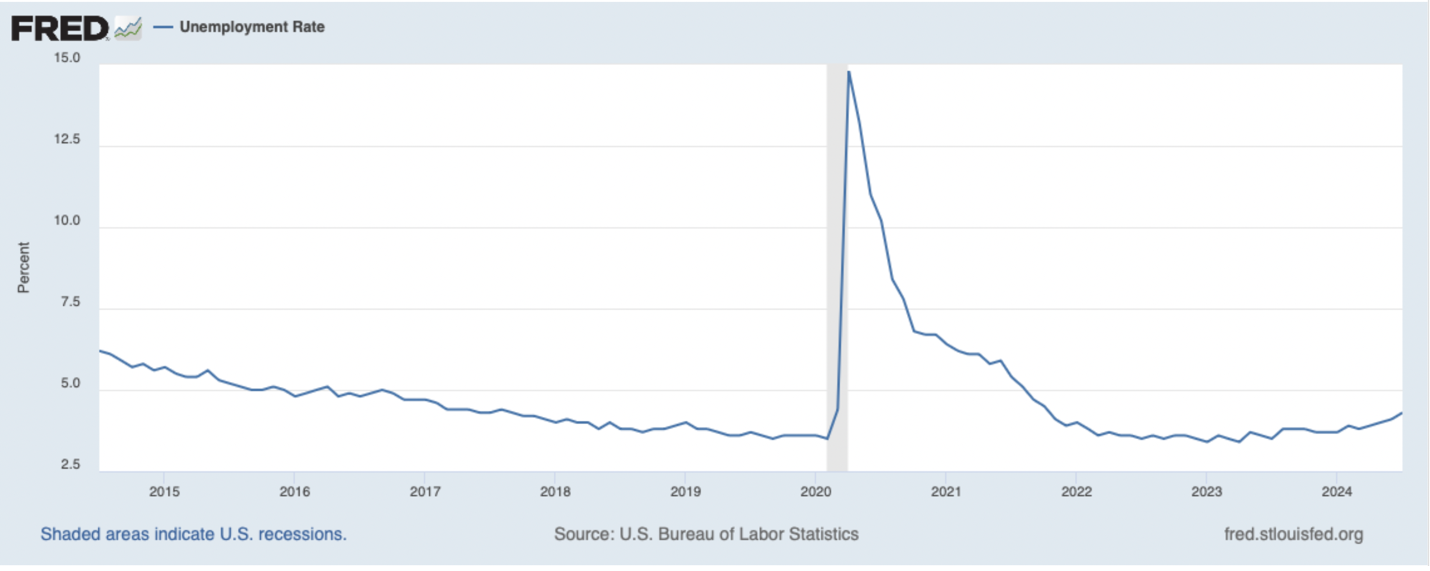

Several months out from the 2024 election, standard economic indicators point to a booming economy. The unemployment rate hovers around 4%, a nearly 50-year low in line with pre-COVID numbers (See Figure 1).

Figure 1

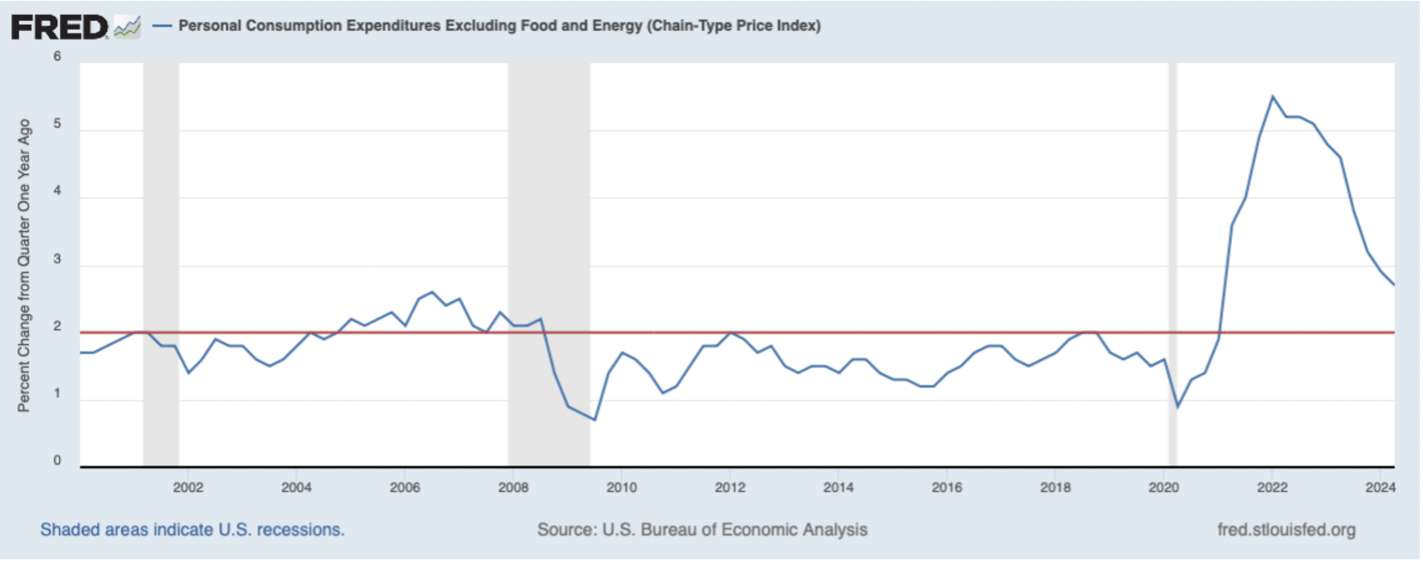

At the same time, the core inflation rate is 2.9%, higher than immediately before COVID but only slightly above the Federal Reserve’s target of 2% per year (See Figure 2).

Figure 2

Economists assume these conditions would spark more optimism than pessimism, but as Dean Yeltekin shared in a recent blog, the opposite is true. The majority of Americans believe the U.S. is in a recession despite these apparently strong economic markers.

From my perspective, this mismatch between perception and reality comes down to one key metric: real wages—the level of wages that takes inflation into account. If real wages grow over time, that means wages are growing faster than prices. If real wages fall over time, wages are growing more slowly than prices.

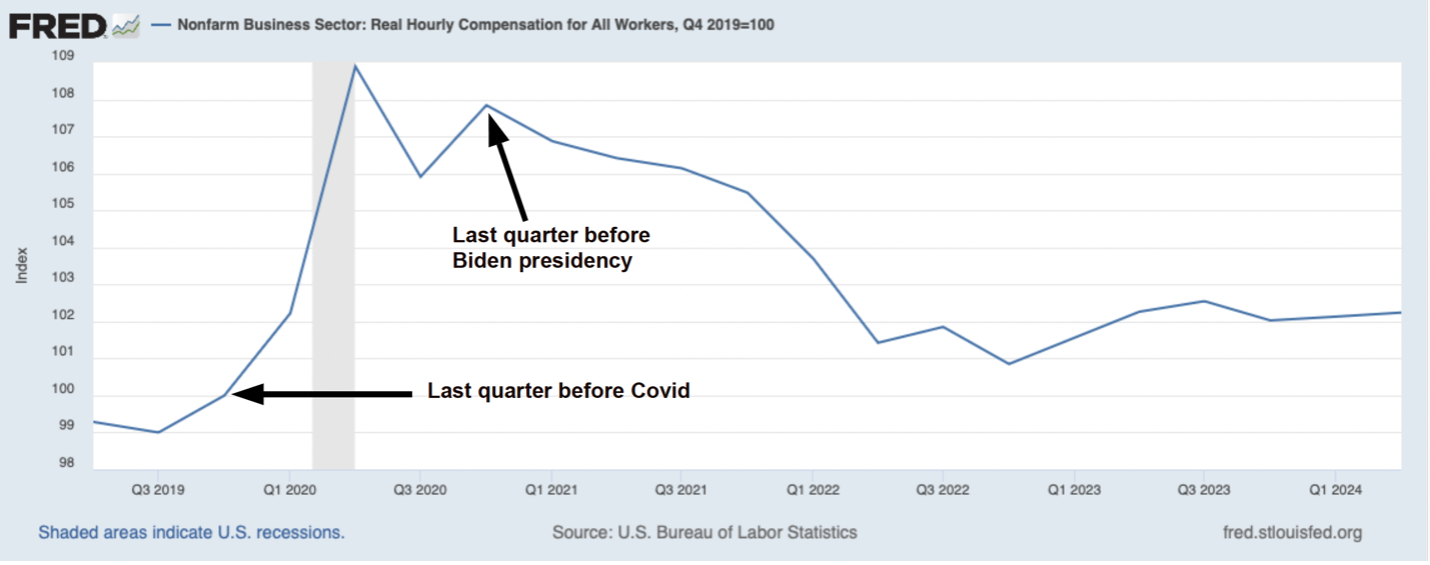

In Figure 3, we see that real wages have fallen sharply during President Biden’s term, with inflation outpacing wage growth by about 5%.

Figure 3

Table 1 (below) depicts the growth in real wages during the first full term of every President since World War II. The decline of real wages in President Biden’s term is unprecedented.

Table 1: Change in Real Compensation in Presidential First Terms

| Presidential Term | Growth in Real Compensation Per Hour |

|---|---|

| Eisenhower 1956 | 15.8% |

| Nixon 1972 | 7.7% |

| Carter 1980 | 2.3% |

| Reagan 1984 | 1.5% |

| Bush 1992 | 4.5% |

| Clinton 1996 | -1.7% |

| Bush 2004 | 5.5% |

| Obama 2012 | 0.0% |

| Trump 2020 | 12.8% |

| Biden 2024 | -5.2% |

The table is based on the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS)’s quarterly data on hourly real compensation. It reports the cumulative growth in real compensation per hour from the fourth quarter preceding the President’s first term to the fourth quarter at the end of his term. (The exception is President Biden, where I use the second quarter of 2024.) I’ve excluded Presidents Truman, Johnson, and Ford because they did not serve full terms.

Markups or Productivity?

Why have real wages fallen so much? There are really only two possible causes: falling productivity and rising markups.

It could be that workers have become less productive over time. For example, we’ve all heard about post-COVID supply chain disruptions, which have made essential inputs like semiconductor chips more expensive for car manufacturers. Using fewer chips means that the same number of workers can’t make as many cars, and so they are less productive. In this kind of context, it’s natural to see a fall in real wages, as businesses simply can’t afford to pay workers as much.

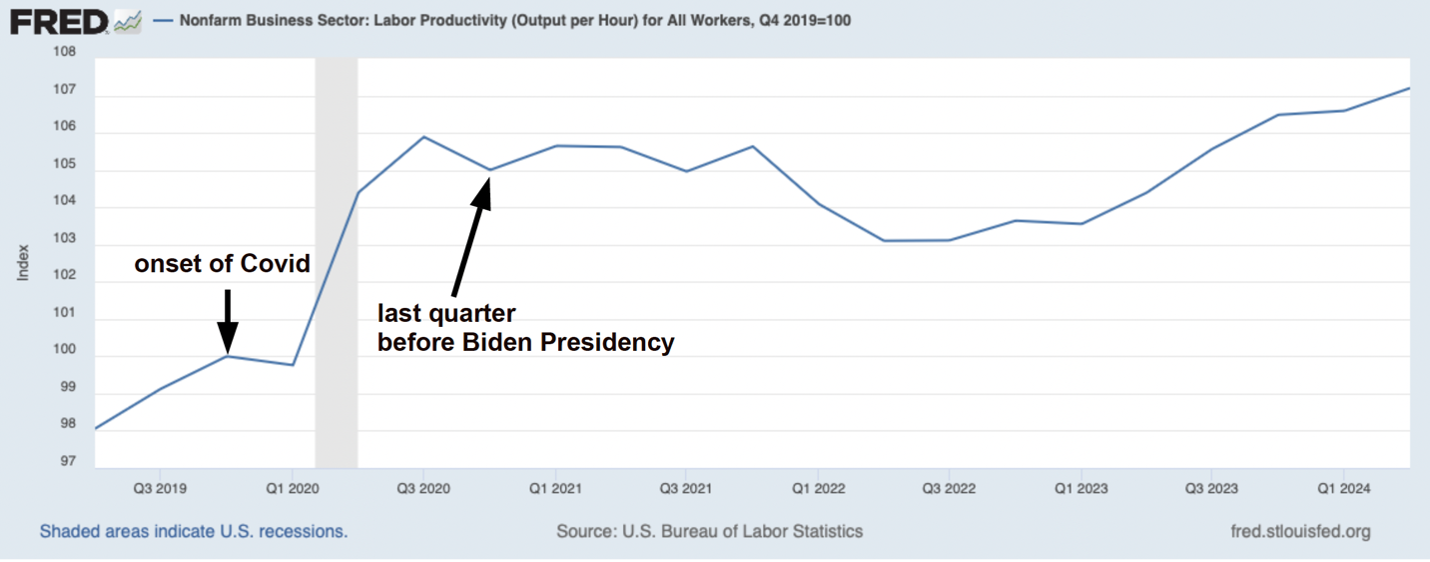

But this story doesn’t work. When we look at the data (see Figure 5), productivity has grown over the past five years.

Figure 4

The decline in real wages since the end of 2020, combined with the rise in productivity, means that firms’ prices have risen markedly (around 7%) relative to their costs over that period. In economists’ language, this means that the firms’ markups—their gaps between prices and costs—have grown substantially.

Symptom of a Big Problem

The rise in markups suggests that there is an important underlying problem with the U.S. economy: Over the past few years, production has become a lot more rewarding as prices have risen faster than costs. In a capitalist system, economic actors should respond rapidly to this incentive. Existing firms should expand production. And new firms should start up. By doing so, they’ll compete up the wages of (relatively scarce) workers and compete down prices. That would automatically keep real wages from falling so much— and also boost economic growth.

The fall in real wages and the associated rise in markups tells us that the economic system is broken. At this time, the “why” is still unclear. But, whatever the source, there is surely cause for deep public concern.

Narayana Kocherlakota is the Louise and Henry Epstein Professor of Business Administration and Professor of Finance at Simon Business School.

Follow the Dean’s Corner blog for more expert commentary on timely topics in business, economics, policy, and management education. To view other blogs in this series, visit the Dean's Corner Main Page.