CEO compensation

CEO compensation

February 2, 2022 | By Sudarshan Jayaraman

Firms offer major compensation packages to attract the cream of the executive crop to the C-suite. But at what cost? According to a report from the Institute for Policy Studies, 80% of CEOs at S&P 500 companies earn 100 times more than their employees’ median salary. For the top 50 companies with the widest wage gap, it would take the median salaried employer up to 1,000 years to earn what their company’s CEO makes in a single year. The gap only continues to widen over time.

In this Q&A, Professor Sudarshan Jayaraman offers his insights on the phenomenon.

Dean Yeltekin: What factors have contributed to the growth in CEO compensation over the past 30 years?

Jayaraman: In a nutshell, it’s the shift from salary to equity compensation that has fueled growth in CEO earnings. The early 1990s saw regulations that called for a $1 million cap on tax deductions for CEO salaries. While the change may have seemed virtuous at the time, there was one major loophole: The eventual law passed by Congress exempted equity compensation like stock options and performance shares from the deductible limit. As a result, many CEOs were willing to take a $0 or $1 annual paycheck if it meant receiving equity compensation in return. With stock prices rising steadily since the 1990s, equity compensation has increased across the board regardless of how a company performs in relation to its competitors.

Dean Yeltekin: Has the COVID-19 pandemic affected CEO compensation?

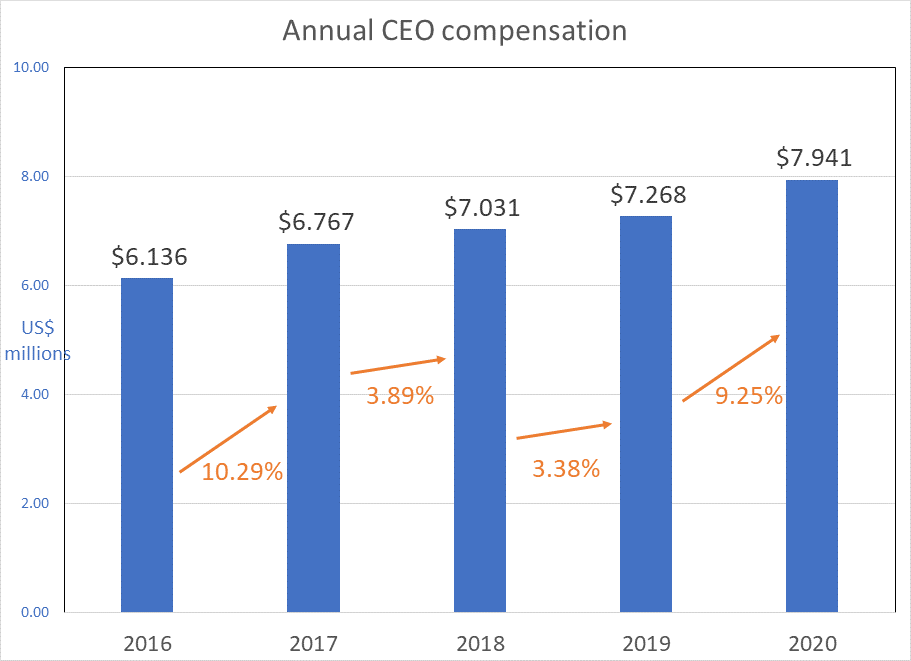

*This chart displays yearly averages of CEO compensation granted by companies that are covered by the S&P Execucomp database and report executive compensation to the SEC. Total compensation includes salary, bonus, restricted stock, and other forms of equity-based compensation (including stock options).

Jayaraman: I ran a quick analysis to compare the growth of CEO compensation in 2020, the most recent year for which data are available, against previous years. Perhaps unsurprisingly, CEOs, on average, got paid about 9.25% more in annual compensation in 2020 compared to 2019. This growth rate is a bit larger than that of the previous two years and similar to the growth from 2016 to 2017.

Opponents of the persistent increase in CEO compensation will reference this kind of data as evidence that CEOs are disconnected from working-class America and that the compensation model is broken. On the other hand, advocates of increasing CEO compensation point out that the onset of the pandemic required CEOs to navigate their companies out of trouble. In other words, the marginal value of leadership was higher during these times than before. By this logic, CEOs should be paid more in return for shouldering a greater burden.

Dean Yeltekin: How might pandemic labor shortages impact CEO compensation going forward?

Jayaraman: As we enter the reporting cycle, firms will be releasing reports on their financial performance from the past year. People are anxious to see if companies place the burden of inflation on their consumers by raising product prices or if they choose to eat the costs out of their own budget. Either way, I would be surprised if CEO compensation changes as a result of shifts in the labor market. Even if CEOs take a pay cut, it would be like the difference between making $31 million and $29.5 million—a barely noticeable dent.

Dean Yeltekin: How should we think about determining an optimal level of CEO compensation?

Jayaraman: In its annual proxy statement, JP Morgan Chase disclosed that its CEO, Jamie Dimon, was compensated $31 million in 2020. Dimon was criticized for taking such a considerable salary when the world was going through a financial and public health crisis, but you’re talking about a massive firm that takes considerable skill and expertise to lead. Let’s imagine a world where everybody gets paid exactly the same. If the CEO and the entry-level worker made the same income, who would sign up to be the CEO? Why would anyone want to take on that kind of risk? Why would anyone want to do the work of innovating? Maybe in the case of JP Morgan Chase, the right amount of CEO compensation is even larger than $31 million. Maybe it’s somewhere between $31 million and the median employee salary. It’s nearly impossible to say.

Economists would respond to this discussion by saying that setting such an optimal level is easy: Just set pay equal to the marginal productivity of CEO labor. But, in reality, we do not get to observe the marginal productivity of CEO labor—or the labor of the median worker. Statements like “This CEO got paid 750 times more than the median worker” make great headlines, but that doesn’t tell me very much. It certainly doesn’t tell me what optimal CEO compensation should be.

Dean Yeltekin: What kind of accountability is possible for overseeing CEO compensation?

Jayaraman: In an ideal world, a firm’s Board of Directors and compensation committee is responsible for holding a CEO accountable to her shareholders. However, there is often very little incentive to go against the CEO because the CEO plays a big role in whether a board member will be re-elected. In addition, many business leaders sit on multiple boards for multiple companies. As a result, we see conflicts of interest that make the Board of Directors less effective. They think, ‘I don’t have an incentive to lower your salary, because you might lower mine.’

Dean Yeltekin: Does CEO compensation correspond to the success of their firm?

Jayaraman: In the early 1980s, a Finnish economist named Bengt Holmström developed a model called Relative Performance Evaluation. Rather than measuring a CEO’s performance against their own company’s total performance, the model provides a framework for evaluating performance relative to its peers. Let’s say a firm makes a 5% return, but so do its peers. In that case, the CEO shouldn’t receive any additional performance-based compensation. And if the peers perform better, the CEO’s performance-based pay should actually be cut. But when you go through the literature, you don’t find that CEO compensation corresponds to relative performance. Commentators have pointed to this lack of relative performance data as evidence that compensation practices are rigged. In a recently published paper, my co-authors and I dig deeper into that disconnect.

Dean Yeltekin: Could you highlight some of the findings from that paper?

Jayaraman: We hypothesize that the lack of evidence in favor of relative performance evaluation might be on account of how peers are defined in the literature – which is based on canned and outdated industry definitions, like “financial services” or “insurance companies,” or “car manufacturers.” We depart from this way of thinking and rely instead on machine learning technologies that sift through thousands of annual SEC reports, assigning a higher product market score to companies with more similar product descriptions in their reports. For example, while Tesla might be popularly known for manufacturing cars, it self-identifies as a technology firm, competing with tech giants like Apple and Microsoft in addition to auto manufacturers like Chrysler and General Motors.

We find that machine learning techniques do a better job of identifying the firm’s peers. In doing so, we uncover evidence that CEOs are indeed being compensated based on Holmström’s relative performance evaluation model. Researchers were previously unable to find this correlation because they didn’t have accurate industry classifications to work with.

While there is still plenty of ground to cover on this subject, emerging technologies have given us the opportunity to make great strides in the past few years.

Sudarshan Jayaraman is the Wesray Professor of Business Administration and a Professor of Accounting at Simon Business School.

Follow the Dean’s Corner blog for more expert commentary on timely topics in business, economics, policy, and management education. To view other blogs in this series, visit the Dean's Corner Main Page.